The federal government’s effort to make postsecondary education more affordable has resulted in a convoluted maze of federal student aid programs including several grant programs, six different types of student loans, nine repayment plans, eight forgiveness programs, and 32 deferment and forbearance options.

This layered approach to education financing has resulted in unprecedented levels of student debt and has created more burden than opportunity for students. To make matters worse, institutions of higher education that receive taxpayer funding are gaming the system by avoiding accountability rules.

A recent article in FORBES notes the findings of a recent GAO report, and what can be done to reverse abuse within the student financial aid system.

The Committee on Education and the Workforce has a solution. The PROSPER Act addresses the issues within the GAO report in three ways:

1. The PROSPER Act streamlines the student aid programs into one grant program, one loan program, and one work-study program to ease confusion for students who are deciding the best options available to responsibly pay for their college education.

2. Pares down the numerous repayment options to two options to help borrowers better manage their debt after graduation.

- One standard 10-year repayment plan; and

- One income-based repayment plan. Borrowers in the IBR plan are required to repay only the principal and interest they would have paid under a standard 10-year plan.

3. Holds institutions accountable by replacing the institutional-level cohort default rate with a program-level loan repayment rate. This targeted approach will increase institutional skin in the game, prepare students for a successful career, and encourage timely and successful repayment of student loans.

By Preston Cooper — May 2, 2018

The complexity of the federal student loan program has long been a nuisance to borrowers. But a new report released by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a federal watchdog, shows that the program’s complexity has also enabled colleges receiving taxpayer money to avoid a key accountability rule. While many observers have focused on the institutions’ chicanery, GAO’s findings also highlight the need to rein in forbearance, a few-questions-asked tool borrowers can use to delay paying their loans.

For colleges that receive student aid funds from taxpayers, the Department of Education calculates the percentage of alumni who default on their student loans within three years of entering repayment. (Default is defined as failure to make a loan payment for 360 days.) If this percentage, known as the “cohort default rate,” rises above a certain threshold, the college may lose access to federal student aid.

Naturally, colleges have an incentive to ensure that, if their students are going to default, they do so after the three-year window has closed. For students who are unable or unwilling to make their student loan payments, loan servicers have the option to place their loans in forbearance for up to – you guessed it – three years. Many students who go into forbearance simply delay a forthcoming default until after the cohort default rate window has closed and their colleges can no longer be held accountable.

The federal government gives loan servicers power to grant a forbearance request for any reason. To that end, many colleges hire “default management consultants” to steer borrowers towards this option. According to GAO, these consultants contacted borrowers and urged them to request forbearance. Some consultants engaged in unethical behavior, such as falsely telling borrowers that defaulting on a student loan would mean losing eligibility for food stamps.

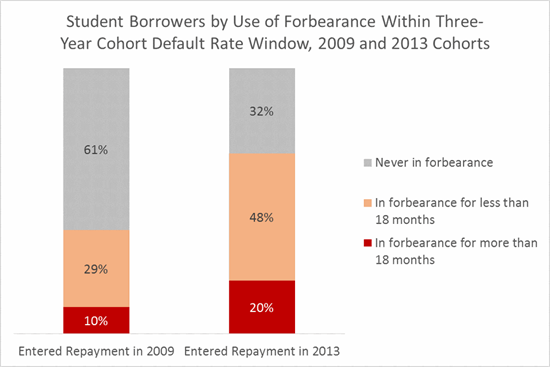

Borrowers are now more likely than not to place their loans into forbearance at least once. For student borrowers who entered repayment in 2013, 68% used forbearance during the three-year cohort default rate window. A fifth used forbearance for more than a year and a half. Such widespread use of forbearance is enough to artificially reduce default rates by several percentage points, and keep afloat many colleges that should have failed the cohort default rate test.

GAO calculated the number of colleges which would have failed the test had cohort default rates excluded borrowers who used forbearance for more than eighteen months. Two hundred sixty-five colleges would have failed that modified test and risked losing access to aid. (Just ten actually failed.) Contrary to perceptions, this is not just a question of for-profit colleges: more than half of the should-have-failed colleges are public or private nonprofit schools.

Observers have drawn attention to the sleaze of the default-management business and problems with the cohort default rate as an accountability metric. But the forbearance fiasco highlights a more uncomfortable reality: how easy it is for student borrowers to avoid paying their loans.

To receive forbearance on their loans, all borrowers need is the approval of their loan servicer. It is not necessary to prove a legitimate hardship to delay making loan payments. Over two and a half million borrowers are currently in forbearance, with most of those forbearances granted at the servicer’s discretion.

In addition to helping colleges avoid sanctions, forbearance also increases total loan payments for borrowers. Interest continues to accrue on loans in forbearance, meaning a borrower who uses forbearance will pay more on his loans over his lifetime. GAO calculates that a borrower who uses forbearance for three years on a $30,000 loan will pay an additional $6,742 in interest.

Rather than ceasing payments on their loans entirely, it’s better for borrowers facing financial difficulty to reduce their monthly payments by choosing a different repayment plan. A borrower can choose a longer term with lower monthly payments, or simply link payments to her income. Tools like forbearance, wherein the borrower stops making payments entirely, should be allowed only in rare circumstances such as severe economic hardship or medical issues.

Ultimately, the issues highlighted by GAO are problems of policymakers’ own making. As forbearance is a perfectly legal option for borrowers, it’s unsurprising that colleges have figured out how to manipulate it to their own advantage. Policymakers who want to stop colleges from gaming the system should make the system less gameable.

To read the full story, click here.

To learn more about the PROSPER Act and all the ways it makes postsecondary education work for students again, click here.